Science

Could “Intense World Theory” Answer Many Of Autism’s Questions?

The boy whose brain could unlock autism

Autism changed Henry Markram’s family. Now his Intense World theory could transform our understanding of the condition.

SOMETHING WAS WRONG with Kai Markram. At five days old, he seemed like an unusually alert baby, picking his head up and looking around long before his sisters had done. By the time he could walk, he was always in motion and required constant attention just to ensure his safety.

“He was super active, batteries running nonstop,” says his sister, Kali. And it wasn’t just boyish energy: When his parents tried to set limits, there were tantrums—not just the usual kicking and screaming, but biting and spitting, with a disproportionate and uncontrollable ferocity; and not just at age two, but at three, four, five and beyond. Kai was also socially odd: Sometimes he was withdrawn, but at other times he would dash up to strangers and hug them.

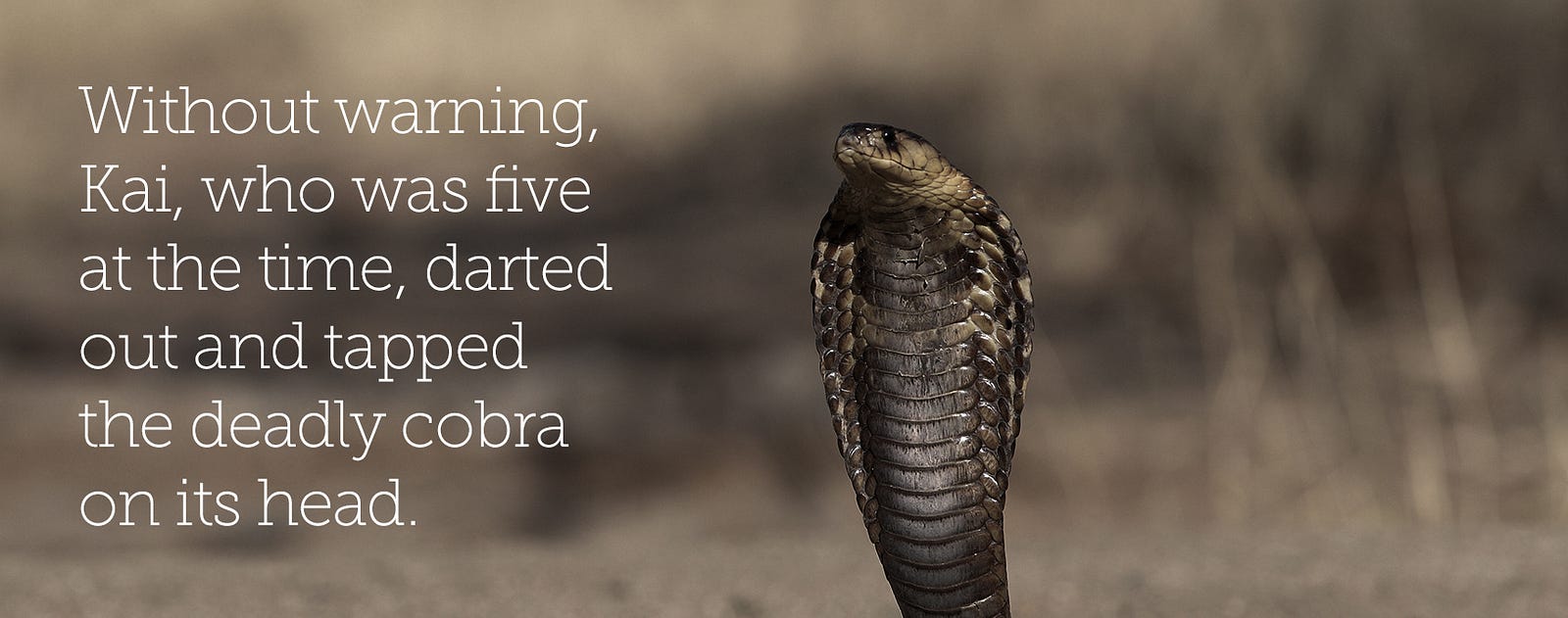

Things only got more bizarre over time. No one in the Markram family can forget the 1999 trip to India, when they joined a crowd gathered around a snake charmer. Without warning, Kai, who was five at the time, darted out and tapped the deadly cobra on its head.

Coping with such a child would be difficult for any parent, but it was especially frustrating for his father, one of the world’s leading neuroscientists. Henry Markram is the man behind Europe’s $1.3 billion Human Brain Project, a gargantuan research endeavor to build a supercomputer model of the brain. Markram knows as much about the inner workings of our brains as anyone on the planet, yet he felt powerless to tackle Kai’s problems.

“As a father and a neuroscientist, you realize that you just don’t know what to do,” he says. In fact, Kai’s behavior—which was eventually diagnosed as autism—has transformed his father’s career, and helped him build a radical new theory of autism: one that upends the conventional wisdom. And, ironically, his sideline may pay off long before his brain model is even completed.

IMAGINE BEING BORN into a world of bewildering, inescapable sensory overload, like a visitor from a much darker, calmer, quieter planet. Your mother’s eyes: a strobe light. Your father’s voice: a growling jackhammer. That cute little onesie everyone thinks is so soft? Sandpaper with diamond grit. And what about all that cooing and affection? A barrage of chaotic, indecipherable input, a cacophony of raw, unfilterable data.

Just to survive, you’d need to be excellent at detecting any pattern you could find in the frightful and oppressive noise. To stay sane, you’d have to control as much as possible, developing a rigid focus on detail, routine and repetition. Systems in which specific inputs produce predictable outputs would be far more attractive than human beings, with their mystifying and inconsistent demands and their haphazard behavior.

This, Markram and his wife, Kamila, argue, is what it’s like to be autistic.

They call it the “intense world” syndrome.

The behavior that results is not due to cognitive deficits—the prevailing view in autism research circles today—but the opposite, they say. Rather than being oblivious, autistic people take in too much and learn too fast. While they may appear bereft of emotion, the Markrams insist they are actually overwhelmed not only by their own emotions, but by the emotions of others.

Consequently, the brain architecture of autism is not just defined by its weaknesses, but also by its inherent strengths. The developmental disorder now believed to affect around 1 percent of the population is not characterized by lack of empathy, the Markrams claim. Social difficulties and odd behavior result from trying to cope with a world that’s just too much.

After years of research, the couple came up with their label for the theory during a visit to the remote area where Henry Markram was born, in the South African part of the Kalahari desert. He says “intense world” was Kamila’s phrase; she says she can’t recall who hit upon it. But he remembers sitting in the rust-colored dunes, watching the unusual swaying yellow grasses while contemplating what it must be like to be inescapably flooded by sensation and emotion.

That, he thought, is what Kai experiences. The more he investigated the idea of autism not as a deficit of memory, emotion and sensation, but an excess, the more he realized how much he himself had in common with his seemingly alien son.

HENRY MARKRAM IS TALL, with intense blue eyes, sandy hair and the air of unmistakable authority that goes with the job of running a large, ambitious, well-funded research project. It’s hard to see what he might have in common with a troubled, autistic child. He rises most days at 4 a.m. and works for a few hours in his family’s spacious apartment in Lausanne before heading to the institute, where the Human Brain Project is based. “He sleeps about four or five hours,” says Kamila. “That’s perfect for him.”

As a small child, Markram says, he “wanted to know everything.” But his first few years of high school were mostly spent “at the bottom of the F class.” A Latin teacher inspired him to pay more attention to his studies, and when a beloved uncle became profoundly depressed and died young—he was only in his 30s, but “just went downhill and gave up”—Markram turned a corner. He’d recently been given an assignment about brain chemistry, which got him thinking. “If chemicals and the structure of the brain can change and then I change, who am I? It’s a profound question. So I went to medical school and wanted to become a psychiatrist.”

Markram attended the University of Cape Town, but in his fourth year of medical school, he took a fellowship in Israel. “It was like heaven,” he says, “It was all the toys that I ever could dream of to investigate the brain.” He never returned to med school, and married his first wife, Anat, an Israeli, when he was 26. Soon, they had their first daughter, Linoy, now 24, then a second, Kali, now 23. Kai came four years afterwards.

During graduate research at the Weizmann Institute in Israel, Markram made his first important discovery, elucidating a key relationship between two neurotransmitters involved in learning, acetylcholine and glutamate. The work was important and impressive—especially so early in a scientist’s career—but it was what he did next that really made his name.

During a postdoc with Nobel laureate Bert Sakmann at Germany’s Max Planck Institute, Markram showed how brain cells that “fire together, wire together.” That had been a basic tenet of neuroscience since the 1940s—but no one had been able to figure out how the process actually worked.

By studying the precise timing of electrical signaling between neurons, Markram demonstrated that firing in specific patterns increases the strength of the synapses linking cells, while missing the beat weakens them. This simple mechanism allows the brain to learn, forging connections both literally and figuratively between various experiences and sensations—and between cause and effect.

Measuring these fine temporal distinctions was also a technical triumph. Sakmann won his 1991 Nobel for developing the required “patch clamp” technique, which measures the tiny changes in electrical activity inside nerve cells. To patch just one neuron, you first harvest a sliver of brain, about 1/3 of a millimeter thick and containing around 6 million neurons, typically from a freshly guillotined rat.

To keep the tissue alive, you bubble it in oxygen, and bathe the slice of brain in a laboratory substitute for cerebrospinal fluid. Under a microscope, using a minuscule glass pipette, you carefully pierce a single cell. The technique is similar to injecting a sperm into an egg for in vitro fertilization—except that neurons are hundreds of times smaller than eggs.

It requires steady hands and exquisite attention to detail. Markram’s ultimate innovation was to build a machine that could study 12 such carefully prepared cells simultaneously, measuring their electrical and chemical interactions. Researchers who have done it say you can sometimes go a whole day without getting one right—but Markram became a master.

Still, there was a problem. He seemed to go from one career peak to another—a Fulbright at the National Institutes of Health, tenure at Weizmann, publication in the most prestigious journals—but at the same time it was becoming clear that something was not right in his youngest child’s head. He studied the brain all day, but couldn’t figure out how to help Kai learn and cope. As he told a New York Times reporter earlier this year, “You know how powerless you feel. You have this child with autism and you, even as a neuroscientist, really don’t know what to do.”

AT FIRST, MARKRAM THOUGHT Kai had attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Once Kai could move, he never wanted to be still. “He was running around, very difficult to control,” Markram says. As Kai grew, however, he began melting down frequently, often for no apparent reason. “He became more particular, and he started to become less hyperactive but more behaviorally difficult,” Markram says. “Situations were very unpredictable. He would have tantrums. He would be very resistant to learning and to any kind of instruction.”

Preventing Kai from harming himself by running into the street or following other capricious impulses was a constant challenge. Even just trying to go to the movies became an ordeal: Kai would refuse to enter the cinema or hold his hands tightly over his ears.

However, Kai also loved to hug people, even strangers, which is one reason it took years to get a diagnosis. That warmth made many experts rule out autism. Only after multiple evaluations was Kai finally diagnosed with Asperger syndrome, a type of autism that includes social difficulties and repetitive behaviors, but not lack of speech or profound intellectual disability.

“We went all over the world and had him tested, and everybody had a different interpretation,” Markram says. As a scientist who prizes rigor, this infuriated him. He’d left medical school to pursue neuroscience because he disliked psychiatry’s vagueness. “I was very disappointed in how psychiatry operates,” he says.

Over time, trying to understand Kai became Markram’s obsession.

It drove what he calls his “impatience” to model the brain: He felt neuroscience was too piecemeal and could not progress without bringing more data together. “I wasn’t satisfied with understanding fragments of things in the brain; we have to understand everything,” he says. “Every molecule, every gene, every cell. You can’t leave anything out.”

This impatience also made him decide to study autism, beginning by reading every study and book he could get his hands on. At the time, in the 1990s, the condition was getting increased attention. The diagnosis had only been introduced into the psychiatric bible, then the DSM III, in 1980. The 1988 Dustin Hoffman film Rain Man, about an autistic savant, brought the idea that autism was both a disability and a source of quirky intelligence into the popular imagination.

The dark days of the mid–20th century, when autism was thought to be caused by unloving “refrigerator mothers” who icily rejected their infants, were long past. However, while experts now agree that the condition is neurological, its causes remain unknown.

The most prominent theory suggests that autism results from problems with the brain’s social regions, which results in a deficit of empathy. This “theory of mind” concept was developed by Uta Frith, Alan Leslie, and Simon Baron-Cohen in the 1980s. They found that autistic children are late to develop the ability to distinguish between what they know themselves and what others know—something that other children learn early on.

In a now famous experiment, children watched two puppets, “Sally” and “Anne.” Sally has a marble, which she places in a basket and then leaves. While she’s gone, Anne moves Sally’s marble into a box. By age four or five, normal children can predict that Sally will look for the marble in the basket first because she doesn’t know that Anne moved it. But until they are much older, most autistic children say that Sally will look in the box because they know it’s there. While typical children automatically adopt Sally’s point of view and know she was out of the room when Anne hid the marble, autistic children have much more difficulty thinking this way.

The researchers linked this “mind blindness”—a failure of perspective-taking—to their observation that autistic children don’t engage in make-believe. Instead of pretending together, autistic children focus on objects or systems—spinning tops, arranging blocks, memorizing symbols, or becoming obsessively involved with mechanical items like trains and computers.

This apparent social indifference was viewed as central to the condition. Unfortunately, the theory also seemed to imply that autistic people are uncaring because they don’t easily recognize that other people exist as intentional agents who can be loved, thwarted or hurt. But while the Sally-Anne experiment shows that autistic people have difficulty knowing that other people have different perspectives—what researchers call cognitive empathy or “theory of mind”—it doesn’t show that they don’t care when someone is hurt or feeling pain, whether emotional or physical. In terms of caring—technically called affective empathy—autistic people aren’t necessarily impaired.

Sadly, however, the two different kinds of empathy are combined in one English word. And so, since the 1980s, this idea that autistic people “lack empathy” has taken hold.

“When we looked at the autism field we couldn’t believe it,” Markram says. “Everybody was looking at it as if they have no empathy, no theory of mind. And actually Kai, as awkward as he was, saw through you. He had a much deeper understanding of what really was your intention.” And he wanted social contact.

The obvious thought was: Maybe Kai’s not really autistic? But by the time Markram was fully up to speed in the literature, he was convinced that Kai had been correctly diagnosed. He’d learned enough to know that the rest of his son’s behavior was too classically autistic to be dismissed as a misdiagnosis, and there was no alternative condition that explained as much of his behavior and tendencies. And accounts by unquestionably autistic people, like bestselling memoirist and animal scientist Temple Grandin, raised similar challenges to the notion that autistic people could never really see beyond themselves.

Markram began to do autism work himself as visiting professor at the University of California, San Francisco in 1999. Colleague Michael Merzenich, a neuroscientist, proposed that autism is caused by an imbalance between inhibitory and excitatory neurons. A failure of inhibitions that tamp down impulsive actions might explain behavior like Kai’s sudden move to pat the cobra. Markram started his research there.

MARKRAM MET HIS second wife, Kamila Senderek, at a neuroscience conference in Austria in 2000. He was already separated from Anat. “It was love at first sight,” Kamila says.

Her parents left communist Poland for West Germany when she was five. When she met Markram, she was pursuing a master’s in neuroscience at the Max Planck Institute. When Markram moved to Lausanne to start the Human Brain Project, she began studying there as well.

Tall like her husband, with straight blonde hair and green eyes, Kamila wears a navy twinset and jeans when we meet in her open-plan office overlooking Lake Geneva. There, in addition to autism research, she runs the world’s fourth largest open-access scientific publishing firm, Frontiers, with a network of over 35,000 scientists serving as editors and reviewers. She laughs when I observe a lizard tattoo on her ankle, a remnant of an adolescent infatuation with The Doors.

When asked whether she had ever worried about marrying a man whose child had severe behavioral problems, she responds as though the question never occurred to her. “I knew about the challenges with Kai,” she says, “Back then, he was quite impulsive and very difficult to steer.”

The first time they spent a day together, Kai was seven or eight. “I probably had some blue marks and bites on my arms because he was really quite something. He would just go off and do something dangerous, so obviously you would have to get in rescue mode,” she says, noting that he’d sometimes walk directly into traffic. “It was difficult to manage the behavior,” she shrugs, “But if you were nice with him then he was usually nice with you as well.”

“Kamila was amazing with Kai,” says Markram, “She was much more systematic and could lay out clear rules. She helped him a lot. We never had that thing that you see in the movies where they don’t like their stepmom.”

At the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL), the couple soon began collaborating on autism research. “Kamila and I spoke about it a lot,” Markram says, adding that they were both “frustrated” by the state of the science and at not being able to help more. Their now-shared parental interest fused with their scientific drives.

They started by studying the brain at the circuitry level. Markram assigned a graduate student, Tania Rinaldi Barkat, to look for the best animal model, since such research cannot be done on humans.

Barkat happened to drop by Kamila’s office while I was there, a decade after she had moved on to other research. She greeted her former colleagues enthusiastically.

She started her graduate work with the Markrams by searching the literature for prospective animal models. They agreed that the one most like human autism involved rats prenatally exposed to an epilepsy drug called valproic acid (VPA; brand name, Depakote). Like other “autistic” rats, VPA rats show aberrant social behavior and increased repetitive behaviors like excessive self-grooming.

But more significant is that when pregnant women take high doses of VPA, which is sometimes necessary for seizure control, studies have found that the risk of autism in their children increases sevenfold. One 2005 study found that close to 9 percent of these children have autism.

Because VPA has a link to human autism, it seemed plausible that its cellular effects in animals would be similar. A neuroscientist who has studied VPA rats once told me, “I see it not as a model, but as a recapitulation of the disease in other species.”

Barkat got to work. Earlier research showed that the timing and dose of exposure was critical: Different timing could produce opposite symptoms, and large doses sometimes caused physical deformities. The “best” time to cause autistic symptoms in rats is embryonic day 12, so that’s when Barkat dosed them.

At first, the work was exasperating. For two years, Barkat studied inhibitory neurons from the VPA rat cortex, using the same laborious patch-clamping technique perfected by Markram years earlier. If these cells were less active, that would confirm the imbalance that Merzenich had theorized.

She went through the repetitious preparation, making delicate patches to study inhibitory networks. But after two years of this technically demanding, sometimes tedious, and time-consuming work, Barkat had nothing to show for it.

“I just found no difference at all,” she told me, “It looked completely normal.” She continued to patch cell after cell, going through the exacting procedure endlessly—but still saw no abnormalities. At least she was becoming proficient at the technique, she told herself.

Markram was ready to give up, but Barkat demurred, saying she would like to shift her focus from inhibitory to excitatory VPA cell networks. It was there that she struck gold.

“There was a difference in the excitability of the whole network,” she says, reliving her enthusiasm. The networked VPA cells responded nearly twice as strongly as normal—and they were hyper-connected. If a normal cell had connections to ten other cells, a VPA cell connected with twenty. Nor were they under-responsive. Instead, they were hyperactive, which isn’t necessarily a defect: A more responsive, better-connected network learns faster.

But what did this mean for autistic people? While Barkat was investigating the cortex, Kamila Markram had been observing the rats’ behavior, noting high levels of anxiety as compared to normal rats. “It was pretty much a gold mine then,” Markram says. The difference was striking. “You could basically see it with the eye. The VPAs were different and they behaved differently,” Markram says. They were quicker to get frightened, and faster at learning what to fear, but slower to discover that a once-threatening situation was now safe.

While ordinary rats get scared of an electrified grid where they are shocked when a particular tone sounds, VPA rats come to fear not just that tone, but the whole grid and everything connected with it—like colors, smells, and other clearly distinguishable beeps.

“The fear conditioning was really hugely amplified,” Markram says. “We then looked at the cell response in the amygdala and again they were hyper-reactive, so it made a beautiful story.”

THE MARKRAMS RECOGNIZED the significance of their results. Hyper-responsive sensory, memory and emotional systems might explain both autistic talents and autistic handicaps, they realized. After all, the problem with VPA rats isn’t that they can’t learn—it’s that they learn too quickly, with too much fear, and irreversibly.

They thought back to Kai’s experiences: how he used to cover his ears and resist going to the movies, hating the loud sounds; his limited diet and apparent terror of trying new foods.

“He remembers exactly where he sat at exactly what restaurant one time when he tried for hours to get himself to eat a salad,” Kamila says, recalling that she’d promised him something he’d really wanted if he did so. Still, he couldn’t make himself try even the smallest piece of lettuce. That was clearly overgeneralization of fear.

The Markrams reconsidered Kai’s meltdowns, too, wondering if they’d been prompted by overwhelming experiences. They saw that identifying Kai’s specific sensitivities preemptively might prevent tantrums by allowing him to leave upsetting situations or by mitigating his distress before it became intolerable. The idea of an intense world had immediate practical implications.

The VPA data also suggested that autism isn’t limited to a single brain network. In VPA rat brains, both the amygdala and the cortex had proved hyper-responsive to external stimuli. So maybe, the Markrams decided, autistic social difficulties aren’t caused by social-processing defects; perhaps they are the result of total information overload.

CONSIDER WHAT IT MIGHT FEEL like to be a baby in a world of relentless and unpredictable sensation. An overwhelmed infant might, not surprisingly, attempt to escape. Kamila compares it to being sleepless, jetlagged, and hung over, all at once. “If you don’t sleep for a night or two, everything hurts. The lights hurt. The noises hurt. You withdraw,” she says.

Unlike adults, however, babies can’t flee. All they can do is cry and rock, and, later, try to avoid touch, eye contact, and other powerful experiences. Autistic children might revel in patterns and predictability just to make sense of the chaos.

At the same time, if infants withdraw to try to cope, they will miss what’s known as a “sensitive period”—a developmental phase when the brain is particularly responsive to, and rapidly assimilates, certain kinds of external stimulation. That can cause lifelong problems.

Language learning is a classic example: If babies aren’t exposed to speech during their first three years, their verbal abilities can be permanently stunted. Historically, this created a spurious link between deafness and intellectual disability: Before deaf babies were taught sign language at a young age, they would often have lasting language deficits. Their problem wasn’t defective “language areas,” though—it was that they had been denied linguistic stimuli at a critical time. (Incidentally, the same phenomenon accounts for why learning a second language is easy for small children and hard for virtually everyone else.)

This has profound implications for autism. If autistic babies tune out when overwhelmed, their social and language difficulties may arise not from damaged brain regions, but because critical data is drowned out by noise or missed due to attempts to escape at a time when the brain actually needs this input.

The intense world could also account for the tragic similarities between autistic children and abused and neglected infants. Severely maltreated children often rock, avoid eye contact, and have social problems—just like autistic children. These parallels led to decades of blaming the parents of autistic children, including the infamous “refrigerator mother.” But if those behaviors are coping mechanisms, autistic people might engage in them not because of maltreatment, but because ordinary experience is overwhelming or even traumatic.

The Markrams teased out further implications: Social problems may not be a defining or even fixed feature of autism. Early intervention to reduce or moderate the intensity of an autistic child’s environment might allow their talents to be protected while their autism-related disabilities are mitigated or, possibly, avoided.

The VPA model also captures other paradoxical autistic traits. For example, while oversensitivities are most common, autistic people are also frequentlyunder-reactive to pain. The same is true of VPA rats. In addition, one of the most consistent findings in autism is abnormal brain growth, particularly in the cortex. There, studies find an excess of circuits called mini-columns, which can be seen as the brain’s microprocessors. VPA rats also exhibit this excess.

Moreover, extra minicolumns have been found in autopsies of scientists who were not known to be autistic, suggesting that this brain organization can appear without social problems and alongside exceptional intelligence.

Like a high-performance engine, the autistic brain may only work properly under specific conditions. But under those conditions, such machines can vastly outperform others—like a Ferrari compared to a Ford.

THE MARKRAMS’ FIRST PUBLICATION of their intense world research appeared in 2007: a paper on the VPA rat in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. This was followed by an overview in Frontiers in Neuroscience. The next year, at the Society for Neuroscience (SFN), the field’s biggest meeting, a symposium was held on the topic. In 2010, they updated and expanded their ideas in a second Frontiers paper.

Since then, more than three dozen papers have been published by other groups on VPA rodents, replicating and extending the Markrams’ findings. At this year’s SFN, at least five new studies were presented on VPA autism models. The sensory aspects of autism have long been neglected, but the intense world and VPA rats are bringing it to the fore.

Nevertheless, reaction from colleagues in the field has been cautious. One exception is Laurent Mottron, professor of psychiatry and head of autism research at the University of Montreal. He was the first to highlight perceptual differences as critical in autism—even before the Markrams. Only a minority of researchers even studied sensory issues before him. Almost everyone else focused on social problems.

But when Mottron first proposed that autism is linked with what he calls “enhanced perceptual functioning,” he, like most experts, viewed this as the consequence of a deficit. The idea was that the apparently superior perception exhibited by some autistic people is caused by problems with higher level brain functioning—and it had historically been dismissed as mere“splinter skills,” not a sign of genuine intelligence. Autistic savants had earlier been known as “idiot savants,” the implication being that, unlike “real” geniuses, they didn’t have any creative control of their exceptional minds. Mottron described it this way in a review paper: “[A]utistics were not displaying atypical perceptual strengths but a failure to form global or high level representations.”

However, Mottron’s research led him to see this view as incorrect. His own and other studies showed superior performance by autistic people not only in “low level” sensory tasks, like better detection of musical pitch and greater ability to perceive certain visual information, but also in cognitive tasks like pattern finding in visual IQ tests.

In fact, it has long been clear that detecting and manipulating complex systems is an autistic strength—so much so that the autistic genius has become a Silicon Valley stereotype. In May, for example, the German software firm SAP announced plans to hire 650 autistic people because of their exceptional abilities. Mathematics, musical virtuosity, and scientific achievement all require understanding and playing with systems, patterns, and structure. Both autistic people and their family members are over-represented in these fields, which suggests genetic influences.

“Our points of view are in different areas [of research,] but we arrive at ideas that are really consistent,” says Mottron of the Markrams and their intense world theory. (He also notes that while they study cell physiology, he images actual human brains.)

Because Henry Markram came from outside the field and has an autistic son, Mottron adds, “He could have an original point of view and not be influenced by all the clichés,” particularly those that saw talents as defects. “I’m very much in sympathy with what they do,” he says, although he is not convinced that they have proven all the details.

Mottron’s support is unsurprising, of course, because the intense world dovetails with his own findings. But even one of the creators of the “theory of mind” concept finds much of it plausible.

Simon Baron-Cohen, who directs the Autism Research Centre at Cambridge University, told me, “I am open to the idea that the social deficits in autism—like problems with the cognitive aspects of empathy, which is also known as ‘theory of mind’—may be upstream from a more basic sensory abnormality.” In other words, the Markrams’ physiological model could be the cause, and the social deficits he studies, the effect. He adds that the VPA rat is an “interesting” model. However, he also notes that most autism is not caused by VPA and that it’s possible that sensory and social defects co-occur, rather than one causing the other.

His collaborator, Uta Frith, professor of cognitive development at University College London, is not convinced. “It just doesn’t do it for me,” she says of the intense world theory. “I don’t want to say it’s rubbish,” she says, “but I think they try to explain too much.”

AMONG AFFECTED FAMILIES, by contrast, the response has often been rapturous. “There are elements of the intense world theory that better match up with autistic experience than most of the previously discussed theories,” says Ari Ne’eman, president of the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, “The fact that there’s more emphasis on sensory issues is very true to life.” Ne’eman and other autistic people fought to get sensory problems added to the diagnosis in DSM-5 — the first time the symptoms have been so recognized, and another sign of the growing receptiveness to theories like intense world.

Steve Silberman, who is writing a history of autism titled NeuroTribes: Thinking Smarter About People Who Think Differently, says, “We had 70 years of autism research [based] on the notion that autistic people have brain deficits. Instead, the intense world postulates that autistic people feel too much and sense too much. That’s valuable, because I think the deficit model did tremendous injury to autistic people and their families, and also misled science.”

Priscilla Gilman, the mother of an autistic child, is also enthusiastic. Her memoir, The Anti-Romantic Child, describes her son’s diagnostic odyssey. Before Benjamin was in preschool, Gilman took him to the Yale Child Study Center for a full evaluation. At the time, he did not display any classic signs of autism, but he did seem to be a candidate for hyperlexia—at age two-and-a-half, he could read aloud from his mother’s doctoral dissertation with perfect intonation and fluency. Like other autistic talents, hyperlexia is often dismissed as a “splinter” strength.

At that time, Yale experts ruled autism out, telling Gilman that Benjamin “is not a candidate because he is too ‘warm’ and too ‘related,’” she recalls. Kai Markram’s hugs had similarly been seen as disqualifying. At twelve years of age, however, Benjamin was officially diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

According to the intense world perspective, however, warmth isn’t incompatible with autism. What looks like antisocial behavior results from being too affected by others’ emotions—the opposite of indifference.

Indeed, research on typical children and adults finds that too much distress can dampen ordinary empathy as well. When someone else’s pain becomes too unbearable to witness, even typical people withdraw and try to soothe themselves first rather than helping—exactly like autistic people. It’s just that autistic people become distressed more easily, and so their reactions appear atypical.

“The overwhelmingness of understanding how people feel can lead to either what is perceived as inappropriate emotional response, or to what is perceived as shutting down, which people see as lack of empathy,” says Emily Willingham. Willingham is a biologist and the mother of an autistic child; she also suspects that she herself has Asperger syndrome. But rather than being unemotional, she says, autistic people are “taking it all in like a tsunami of emotion that they feel on behalf of others. Going internal is protective.”

At least one study supports this idea, showing that while autistic people score lower on cognitive tests of perspective-taking—recall Anne, Sally, and the missing marble—they are more affected than typical folks by other people’s feelings. “I have three children, and my autistic child is my most empathetic,” Priscilla Gilman says, adding that when her mother first read about the intense world, she said, “This explains Benjamin.”

Benjamin’s hypersensitivities are also clearly linked to his superior perception. “He’ll sometimes say, ‘Mommy, you’re speaking in the key of D, could you please speak in the key of C? It’s easier for me to understand you and pay attention.”

Because he has musical training and a high IQ, Benjamin can use his own sense of “absolute pitch”—the ability to name a note without hearing another for comparison—to define the problem he’s having. But many autistic people can’t verbalize their needs like this. Kai, too, is highly sensitive to vocal intonation, preferring his favorite teacher because, he explains, she “speaks soft,” even when she’s displeased. But even at 19, he isn’t able to articulate the specifics any better than that.

ON A RECENT VISIT to Lausanne, Kai wears a sky blue hoodie, his gray Chuck Taylor–style sneakers carefully unlaced at the top. “My rapper sneakers,” he says, smiling. He speaks Hebrew and English and lives with his mother in Israel, attending a school for people with learning disabilities near Rehovot. His manner is unselfconscious, though sometimes he scowls abruptly without explanation. But when he speaks, it is obvious that he wants to connect, even when he can’t answer a question. Asked if he thinks he sees things differently than others do, he says, “I feel them different.”

He waits in the Markrams’ living room as they prepare to take him out for dinner. Henry’s aunt and uncle are here, too. They’ve been living with the family to help care for its newest additions: nine-month-old Charlotte and Olivia, who is one-and-a-half years old.

“It’s our big patchwork family,” says Kamila, noting that when they visit Israel, they typically stay with Henry’s ex-wife’s family, and that she stays with them in Lausanne. They all travel constantly, which has created a few problems now and then. None of them will ever forget a tantrum Kai had when he was younger, which got him barred from a KLM flight. A delay upset him so much that he kicked, screamed, and spat.

Now, however, he rarely melts down. A combination of family and school support, an antipsychotic medication that he’s been taking recently, and increased understanding of his sensitivities has mitigated the disabilities Kai associated with his autism.

“I was a bad boy. I always was hitting and doing a lot of trouble,” Kai says of his past. “I was really bad because I didn’t know what to do. But I grew up.” His relatives nod in agreement. Kai has made tremendous strides, though his parents still think that his brain has far greater capacity than is evident in his speech and schoolwork.

As the Markrams see it, if autism results from a hyper-responsive brain, the most sensitive brains are actually the most likely to be disabled by our intense world. But if autistic people can learn to filter the blizzard of data, especially early in life, then those most vulnerable to the most severe autism might prove to be the most gifted of all.

Markram sees this in Kai. “It’s not a mental retardation,” he says, “He’s handicapped, absolutely, but something is going crazy in his brain. It’s a hyper disorder. It’s like he’s got an amplification of many of my quirks.”

One of these involves an insistence on timeliness. “If I say that something has to happen,” he says, “I can become quite difficult. It has to happen at that time.”

He adds, “For me it’s an asset, because it means that I deliver. If I say I’ll do something, I do it.” For Kai, however, anticipation and planning run wild. When he travels, he obsesses about every move, over and over, long in advance. “He will sit there and plan, okay, when he’s going to get up. He will execute. You know he will get on that plane come hell or high water,” Markram says. “But he actually loses the entire day. It’s like an extreme version of my quirks, where for me they are an asset and for him they become a handicap.”

If this is true, autistic people have incredible unrealized potential. Say Kai’s brain was even more finely tuned than his father’s, then it might give him the capacity to be even more brilliant. Consider Markram’s visual skills. Like Temple Grandin, whose first autism memoir was titled Thinking In Pictures, he has stunning visual abilities. “I see what I think,” he says, adding that when he considers a scientific or mathematical problem, “I can see how things are supposed to look. If it’s not there, I can actually simulate it forward in time.”

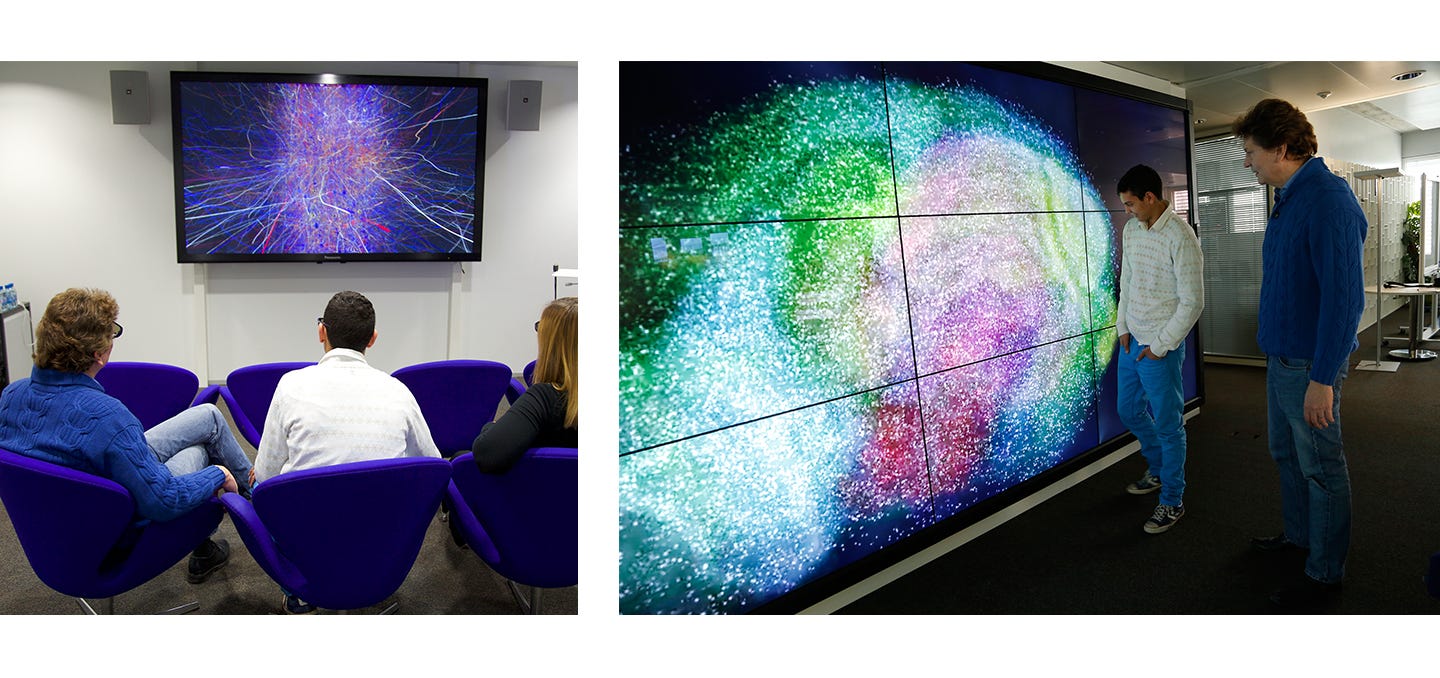

At the offices of Markram’s Human Brain Project, visitors are given a taste of what it might feel like to inhabit such a mind. In a small screening room furnished with sapphire-colored, tulip-shaped chairs, I’m handed 3-D glasses. The instant the lights dim, I’m zooming through a brightly colored forest of neurons so detailed and thick that they appear to be velvety, inviting to the touch.

The simulation feels so real and enveloping that it is hard to pay attention to the narration, which includes mind-blowing facts about the project. But it is also dizzying, overwhelming. If this is just a smidgen of what ordinary life is like for Kai it’s easier to see how hard his early life must have been. That’s the paradox about autism and empathy. The problem may not be that autistic people can’t understand typical people’s points of view—but that typical people can’t imagine autism.

Critics of the intense world theory are dismayed and put off by this idea of hidden talent in the most severely disabled. They see it as wishful thinking, offering false hope to parents who want to see their children in the best light and to autistic people who want to fight the stigma of autism. In some types of autism, they say, intellectual disability is just that.

“The maxim is, ‘If you’ve seen one person with autism, you’ve seen one person with autism,’” says Matthew Belmonte, an autism researcher affiliated with the Groden Center in Rhode Island. The assumption should be that autistic people have intelligence that may not be easily testable, he says, but it can still be highly variable.

He adds, “Biologically, autism is not a unitary condition. Asking at the biological level ‘What causes autism?’ makes about as much sense as asking a mechanic ‘Why does my car not start?’ There are many possible reasons.” Belmonte believes that the intense world may account for some forms of autism, but not others.

Kamila, however, insists that the data suggests that the most disabled are also the most gifted. “If you look from the physiological or connectivity point of view, those brains are the most amplified.”

The question, then, is how to unleash that potential.

“I hope we give hope to others,” she says, while acknowledging that intense-world adherents don’t yet know how or even if the right early intervention can reduce disability.

The secret-ability idea also worries autistic leaders like Ne’eman, who fear that it contains the seeds of a different stigma. “We agree that autistic people do have a number of cognitive advantages and it’s valuable to do research on that,” he says. But, he stresses, “People have worth regardless of whether they have special abilities. If society accepts us only because we can do cool things every so often, we’re not exactly accepted.”

The MARKRAMS ARE NOW EXPLORING whether providing a calm, predictable early environment—one aimed at reducing overload and surprise—can help VPA rats, soothing social difficulties while nurturing enhanced learning. New research suggests that autism can be detected in two-month-old babies, so the treatment implications are tantalizing.

So far, Kamila says, the data looks promising. Unexpected novelty seems to make the rats worse—while the patterned, repetitive, and safe introduction of new material seems to cause improvement.

In humans, the idea would be to keep the brain’s circuitry calm when it is most vulnerable, during those critical periods in infancy and toddlerhood. “With this intensity, the circuits are going to lock down and become rigid,” says Markram. “You want to avoid that, because to undo it is very difficult.”

For autistic children, intervening early might mean improvements in learning language and socializing. While it’s already clear that early interventions can reduce autistic disability, they typically don’t integrate intense-world insights. The behavioral approach that is most popular—Applied Behavior Analysis—rewards compliance with “normal” behavior, rather than seeking to understand what drives autistic actions and attacking the disabilities at their inception.

Research shows, in fact, that everyone learns best when receiving just the right dose of challenge—not so little that they’re bored, not so much that they’re overwhelmed; not in the comfort zone, and not in the panic zone, either. That sweet spot may be different in autism. But according to the Markrams, it is different in degree, not kind.

Markram suggests providing a gentle, predictable environment. “It’s almost like the fourth trimester,” he says.

“To prevent the circuits from becoming locked into fearful states or behavioral patterns you need a filtered environment from as early as possible,” Markram explains. “I think that if you can avoid that, then those circuits would get locked into having the flexibility that comes with security.”

Creating this special cocoon could involve using things like headphones to block excess noise, gradually increasing exposure and, as much as possible, sticking with routines and avoiding surprise. If parents and educators get it right, he concludes, “I think they’ll be geniuses.”

IN SCIENCE, CONFIRMATION BIAS is always the unseen enemy. Having a dog in the fight means you may bend the rules to favor it, whether deliberately or simply because we’re wired to ignore inconvenient truths. In fact, the entire scientific method can be seen as a series of attempts to drive out bias: The double-blind controlled trial exists because both patients and doctors tend to see what they want to see—improvement.

At the same time, the best scientists are driven by passions that cannot be anything but deeply personal. The Markrams are open about the fact that their subjective experience with Kai influences their work.

But that doesn’t mean that they disregard the scientific process. The couple could easily deal with many of the intense world critiques by simply arguing that their theory only applies to some cases of autism. That would make it much more difficult to disprove. But that’s not the route they’ve chosen to take. In their 2010 paper, they list a series of possible findings that would invalidate the intense world, including discovering human cases where the relevant brain circuits are not hyper-reactive, or discovering that such excessive responsiveness doesn’t lead to deficiencies in memory, perception, or emotion. So far, however, the known data has been supportive.

But whether or not the intense world accounts for all or even most cases of autism, the theory already presents a major challenge to the idea that the condition is primarily a lack of empathy, or a social disorder. Intense world theory confronts the stigmatizing stereotypes that have framed autistic strengths as defects, or at least as less significant because of associated weaknesses.

And Henry Markram, by trying to take his son Kai’s perspective—and even by identifying so closely with it—has already done autistic people a great service, demonstrating the kind of compassion that people on the spectrum are supposed to lack. If the intense world does prove correct, we’ll all have to think about autism, and even about typical people’s reactions to the data overload endemic in modern life, very differently.

Autism And Motor Skills Correlate To Improved Adaptive Behaviors

Parents of children with autism spectrum disorders often face greater challenges finding the best learning therapies for their child. A new study looks at children with autism who have better fine motor skills and if having those skills improves learning development. The researchers found that the participants with higher levels of fine motor skills did indeed display stronger daily living skills including better social and communication abilities.

Autistic children with better gross motor skills tended to have stronger daily living skills as well.

Results of the study suggests that helping children with autism develop stronger fine motor skills may improve their adaptive behavior skills as well.

Fine motor skills involve the small muscles of the body that enable such functions as writing, grasping small objects, and fastening clothing. They involve strength, control and dexterity.

Gross motor skills refer to movements that involve large muscle groups and are generally more broad and energetic than fine motor movements. These may include walking, kicking, jumping, and climbing stairs.

The study, led by Megan MacDonald, PhD, of the School of Biological and Population Health Sciences at Oregon State University, looked at whether autistic children’s motor skills were related to their adaptive behavior skills.

Researchers studied 233 children, aged 1 to 4, who had varying diagnoses of developmental delays or disorders.

Among these children, 172 had autism spectrum disorder, 22 had pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), and 39 had developmental delays that were not related to autism.

The researchers assessed the children’s development with an instrument that measures their gross motor skills, fine motor skills, visual reception (nonverbal problem solving), receptive language (comprehending/listening/understanding language) and expressive language (expressing one’s self through language).

Then the researchers used a different test to assess the children’s adaptive behavior skills, which included overall behavior, daily living skills, communication skills and adaptive social skills.

The children’s age, non-verbal problem-solving skills and the severity of their disorder were taken into account.

The researchers found that the children’s levels of fine motor skills predicted how well they scored on all the sections of the adaptive behavior skills assessment.

In addition, the children’s motor skills predicted how well the children did with daily living skills.

The children who had weaker fine or gross motor skills also had greater difficulties with adaptive behavior skills.

“The fine and gross motor skills are significantly related to adaptive behavior skills in young children with autism spectrum disorder,” the researchers wrote.

“Motor skills need to be considered and included in early intervention programming,” they wrote.

Glen Elliott, MD, PhD, a clinical professor at the Stanford University Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, offered his perspectives on the study’s findings.

“This study nicely demonstrates that, on average, children with autism show a correlation between fine- and gross-motor skills and a range of daily living skills and adaptive behaviors,” Dr. Elliott said.

“The authors imply that this may suggest the value of emphasizing early intervention on motor skills along with other areas of deficits,” he said.

“However, it is possible that they are confounding correlation with causation: that is, their observations might equally reflect some other factor, such as overall developmental delays that result in both delayed motor skills and delayed adaptive behaviors,” Dr. Elliott suggested.

“Still, given the increasing evidence of the importance of early interventions in help maximize ultimate outcomes in children with autism, research to explore the usefulness of interventions focusing on motor skills well might be merited,” he said.

This study was published in the November issue of Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders.

Related articles

- Autistic children with better motor skills more adept at socializing (sciencedaily.com)

- Atypical Movements in Autism Spectrum Disorders (conorcaffrey.wordpress.com)

- How is the Cerebellum Linked to Autism Spectrum Disorders? (psychologytoday.com)

Social Thinking Skills At The Crescent J Ranch Helps Autistic Teens

Forever Florida Teaches Teens With Autism

Teens with Autism learn the secrets of ‘Social Thinking’ from experts in the field–Horses and Cows!

Part of the herd at Forever Florida’s Crescent J Ranch, Charolais bulls help autistic adolescents learn social thinking skills. In this video, the bovines are interacting with a new Equi-Spirit horse ball while students on the side-lines interpret their social behavior and responses to a novel object.

KENANSVILLE, FLORIDA – Who could be better at teaching subtle non-verbal communication skills than living, breathing beings that depend solely on such skills for survival and success in navigating life in a socially complex community?

Dean Van Camp, left, and Sandra Wise, second from left, introduce special folks—young and old, burdened, weary or worried—to a special breed of native horses born and raised on the 4,700 acre ranch of 2010 Central Florida Humanitarians, Bill and Margaret Broussard, at right.

Equines and bovines have perfected the use of “body language” and demonstrate exquisite non-verbal communication skills in managing their own social exchanges.

Perhaps more striking, however, is the fact that they, as animals of prey, have also learned to use these skills to operate in a world which is alien to them—that is, the world of humans—who happen to be predators. That accomplishment, indeed, qualifies them as experts in the field.

So on a sunny day last summer, eleven enthusiastic high school students who have been diagnosed with a form of high-functioning Autism called Asperger’s Syndrome, left their base camp at College Internship Program’s summer retreat in Melbourne and headed out to their temporary “home on the range,” that is, the Crescent J Ranch on the grounds of Forever Florida, the 4700-acre wilderness preserve in Osceola County. They were ready for their first lesson in social graces—equine /bovine style.

Two teens with Asperger’s Syndrome debrief an equine-assisted learning session focused on social thinking and non-verbal communication skills. The video interview above was conducted four days after the session. Note how the young man is “reliving” his experience during the interview, as reflected in his body language, precisely mirroring the placement of his arms during the original experience four days earlier. This ability to bring back the experience with such perfect body memory reflects the emotional impact of this encounter.

College Internship Program Prepares Students With High-functioning Autism

The students, who came from locations as far away as Germany, were participating in a summer camp experience hosted by the Brevard Campus of College Internship Program (CIP), a post-secondary educational experience which prepares young adults with Asperger’s, ADHD and other learning differences for success in life.

The College Internship Program at the Brevard Center provides individualized, post-secondary academic, internship and independent living experiences for young adults with Asperger’s Syndrome and other Learning Differences.

CIP was founded by Dr. Michael McManmon,who has a unique perspective as he himself was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome and grew up in a large family with several individuals on the spectrum. When enrolled in one of the CIP programs—there are six across the country—students attend local colleges or take part in career development workshops along with individualized social, academic, career and life skills supports.

The summer program gives these youngsters, age 16 to 19, a taste of independence while residing on a college campus. The students learn that college is not all about academics; it’s about fostering connections and having fun while learning the necessary skills to succeed. One of those skills is called “social thinking,” which is what we do when we interact with others—that is, we think about them and about what they are thinking. This determines how we behave, and how we behave, of course, drives the responses we get from others.

Good ‘Social Thinking’ Skills Can Determine Success In Life

Michelle Garcia Winner, who coined the term Social Thinking more than 15 years ago, states, “Whether we are with friends, sending an email, in a classroom or at the grocery store, we take in the thoughts, emotions and intentions of the people we are interacting with.

Most of us have developed our communications sense from birth onwards, steadily observing and acquiring social information and learning how to respond to people. Because social thinking is an intuitive process, we usually take it for granted. But for many individuals, this process is anything but natural. And this often has nothing to do with conventional measures of intelligence. In fact, many people score high on IQ and standardized tests, yet do not intuitively learn the nuances of social communication and interaction.”

The social thinking challenges which Winner refers to are common in individuals with autism spectrum disorders and similar diagnoses. But it is also true that many individuals who have never received a diagnosis experience social learning difficulties. People with such deficits are often perceived as rude and self-centered, as they have difficulty detecting when their conversational partner is becoming boring or when someone has extended a kindness to them which should be acknowledged. Hence, they are often negatively perceived and can easily become targets of bullying, which can lead to social isolation and depression.

The Beginning of an Innovative Approach to Teaching Social Thinking Skills

To address such deficits, experts in various fields, such as education and mental health, have developed methods to build social interaction skills in students and adults. Some learning programs involve classroom lectures and discussions with accompanying cartoons or story boards; some employ role-play; others focus on watching and debriefing movies and videos of human interactions. All of these approaches attempt to teach individuals how to process social information and recognize how their own behaviors are being perceived.

Left to right, Dr. Michael McManmon, founder of CIP, Dr. Temple Grandin and Dr. Sandra Wise at the recent U.S. Autism and Asperger’s Association World Conference in Denver where Drs. Grandin and Wise gave presentations describing the importance of hands-on experiential approaches to the treatment of autism.

As I observed one of these social thinking classes at the Brevard CIP campus in April, I was struck with the thought that students with Asperger’s might be able to learn these skills, which are primarily non-verbal, much more effectively if we could remove the verbal component of social exchange during the actual learning experience. This would eliminate the need to decipher the subtleties of spoken language (idioms, etc.), which are often confusing for this population, and would bypass the need to formulate a verbal response, which can easily pull individuals with Asperger’s off task. Since many of the difficulties that these students run into in social situations involve missing important non-verbal social cues, I thought to myself, why not pair them up with the non-verbal experts I had been associated with for the past ten years—horses and cows?

Hence began the planning for “Social Thinking Skills—Straight from the Horse’s Mouth.”

Why Horses and Cows?

One only has to look to the work of Temple Grandin, a person with Autism herself, who has earned a Ph.D. and has distinguished herself as an expert not only in the field of animal science, but also in the field of treatment for Autism, to understand the benefits that can be accrued from immersing oneself in the equine and bovine world.

The sole method of communication in that world is body language. As noted above, it’s important to remember that horses and cows are animals of prey—a characteristic which has required them to develop uncanny skills in detecting and sending precise non-verbal signals.

It made sense to me to turn these students with Asperger’s over to the experts in the field. So on that sunny summer day in June, we literally headed out to the “field” far in the back of the Crescent J Ranch.

The Students Strike Out to Find a ‘Home on the Range’

James, a young student with Asperger’s, creates a relationship with this naïve colt by monitoring his own body language, allowing the colt to approach him, on its own terms, from behind.

The students received no specific instruction as they rode in a safari coach to a pasture about three miles back into the beautiful natural setting at Forever Florida where they encountered one of several groups of Florida Cracker horses on the Crescent J, which boasts the largest herd of that breed, which is especially suited forequine-assisted psychotherapy, in the world.

Here the students entered the non-verbal world of a young stallion, Tequila, and his herd of mares. A number of colts had already been born and numerous other mares were still pregnant. The students were simply told to “go mingle” and communicate with these beautiful animals, who are quite social, despite the fact that the majority of the mares have never been trained or had any type of restraint placed on them.

The colts, which are born naturally in the field, had never been touched by humans. The students spent about 45 minutes in this pasture then visited a second pasture where a similar component of mares and colts, led by the stallion Pretty Boy, was living in community with a herd of cattle and calves, headed by one very large bull.

Due to their keen awareness skills, patience, and consistency, Bryson and Lizzie are able to completely capture the trust of these two horses–the stallion Pretty Boy, who comfortably rests his head in Bryson’s arm, and a pregnant mare, who feels safe enough to reach out physically and make contact with Lizzie.

So what happened when these students, who have difficulty with social thinking skills, introduced themselves to the experts in the field?

One young student, Bryson, described his experience with the stallion Pretty Boy: “We had a conversation in our heads but we disagreed. He knew I was only there for the experience so he let me be there and didn’t give me too much trouble. He said to me, ‘You are out-numbered. I’m glad you’re here to visit because we aren’t that different from each other. Horses like us like to run. People like you like to relax. And relaxing is kind of like running.’”

Bryson’s efforts were clearly aimed at trying to read what Pretty Boy might have been thinking—that’s the essence of social thinking.

Bryson continued, “The horse’s head was cutting off the circulation in my arm.” When asked why he didn’t move his arm, he stated, “Because I was feeling the love from the horse.

He had love for me and I had love for him.” Bryson was profoundly affected by this interaction with the stallion. In the debriefing he repeatedly spoke about how his arm was falling asleep under Pretty Boy’s head but he was so happy to be holding him that he didn’t mind so much.

A Cracker colt’s first close encounter with a human: By reading and sending appropriate body language cues and using “social thinking” skills to anticipate the colt’s reactions, Alex, a high school student with Asperger’s Syndrome, was able to create a trusting relationship.

He also talked about how calm and clear his mind felt just being in the “wide-open spaces” of the natural wilderness. He reported that he has a hard time learning in other environments because there are so many distractions, but out at the ranch he felt like he could take it all in and “everything made sense.”

Sarah, who now attends CIP fulltime, told us, “I want to be with the horses because they help me learn about human behavior with their bodies. I want to teach special education and I need to know about body language for that. Horses are therapeutic. They make us feel more comfortable than sitting in a classroom.”

Another student added, “I can learn out here. With the horses there’s less distraction.”

Horses and Cows Prove to be Great Teachers, So What’s Next?

Due to the success of this summer camp venture and other similar CIP student and staff visits, The Equine Education Center, Forever Florida’s division that directs the equine-assisted mental health programs, is now staging a weekly equine-assisted learning experience as part of the social thinking curriculum for a number of CIP students this fall semester.

After successfully utilizing body language to engage horses, students listen to a short briefing regarding the social nature of cattle, the next population with which the students tried out their non-verbal communication skills.

Our hope is that these special students will gain confidence in their ability to learn and practice social thinking skills by interacting in a non-threatening environment where non-verbal language—which is, after all, the true language of relationships—is the onlylanguage expressed and comprehended.

They can then build on this confidence to develop the full range of social communication skills needed to navigate in that seemingly alien world known as human relationships.

Autism: It’s Different For Girls, Part 2

HOW AUTISM IS DIFFERENT IN GIRLS VS. BOYS

![[image]](https://i0.wp.com/si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/PJ-BO135_LAB_G_20130506154333.jpg)

A baby named Harper participated an eye-tracking research at the Marcus Autism Center in Atlanta.

Why do boys get diagnosed with autism four times as often as girls?

New research, including some of the latest data from the International Society for Autism Research annual conference last week, addresses this question, one of the biggest mysteries in this field. A growing consensus is arguing that sex differences exist in genetic susceptibility, brain development and social learning in autism—and they are meaningful to our understanding of the disorder and how it will be treated.

Yale University researchers presented results showing that being female appears to provide genetic protection against autism. Meanwhile, scientists at Emory University showed in preliminary work that boys and girls with autism learn social information differently, which leads to divergent success in interactions with other people.

The new data, together with previously published studies, suggest that sex should be taken into account in diagnosing and in creating individualized treatment plans, according to experts.

Autism, a developmental disorder characterized by deficits in social skills and repetitive behaviors, affects more than 1% of the population. It has long been known to be diagnosed more often in boys.

Yet girls often appear to have more severe autism. The ratio, about four boys to every one girl overall, becomes even more lopsided when intelligence is taken into account. At higher intelligence levels, boys with autism often outnumber girls eight or 10 to one, say researchers.

Why this ratio exists and how much it is skewed by misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis in girls isn’t clear. More and more, however, scientists think the sex distribution is meaningful.

“It’s such an important biological clue—why do we have this excess in boys?” said Geraldine Dawson, the chief science officer of Autism Speaks, a research funding and advocacy group.

Sex differences in autism and related disorders were relatively ignored until recently and still aren’t well understood. The small number of girls who have the disorder meant that studies often didn’t include enough girls to be able to reliably examine sex differences. Often, girls were excluded from studies altogether.

Understanding sex differences is important to getting the right diagnosis and treatment, said Christopher Gillberg, a child and adolescent psychiatry professor at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. Because experts’ understanding of the typical features of the condition is primarily based on research with boys, girls may be missed or misdiagnosed, he said. Some evidence suggests that girls are diagnosed, on average, later than boys.

In addition, the clinical picture for children with an autism-spectrum disorder is often complex. Most have other conditions as well, like attention-deficit hyperactivity disorders, sleep problems or epilepsy, which may affect their functioning, Dr. Gillberg said.

He and his colleagues evaluated 100 girls between the ages of 3 and 18 who had social or attention deficits. Forty-seven were diagnosed with autism. As well, 80% of those with autism also could be diagnosed with ADHD. Virtually all the girls had depression, anxiety and family relationship problems.

Understanding sex differences also has implications for elucidating the condition more broadly. Experts speculated that perhaps boys were somehow more vulnerable to autism because of, for instance, genes, hormones or different ways their brains are wired.

From a genetic standpoint, however, there is growing evidence that boys aren’t more susceptible to autism, but rather girls are more protected from it. Yale researchers added to this thinking with new findings presented last week in which they looked at the DNA of several thousand children with autism.

They found that girls actually had substantially more high-risk genetic mutations associated with autism than boys, on average twice as many. Yet, because girls develop autistic features less often, something about being female is protective against the condition, said Stephan Sanders, a postdoctoral fellow at Yale University who presented the work.

The Yale scientists then wondered if the males and females might actually be experiencing two distinct disorders at the genetic level. But further research led them to conclude that boys and girls appear to be suffering from the same ailment, Mr. Sanders said.

There is also early evidence that even though boys and girls may have the same condition, the way they process information could lead to different outcomes. For instance, studies of social learning, the core process that appears affected in children with autism-spectrum disorders, have found differences between the two sexes.

Kids with autism tend to look more at people’s mouths, while typically developing children look more at the eyes, Ami Klin, head of Emory University’s and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta’s Marcus Autism Center, and others have found. The thinking was that eyes tend to provide a lot of social information, such as emotion or interest, and the kids with autism miss out on a lot of this information, which contributes to their social impairment in interactions with others.

But in new work, Marcus researchers are comparing sex differences in eye gaze in typically developing children and those with autism, and have been surprised by the findings. The scientists showed six film clips involving social interactions, like boys playing baseball or kids chatting, to 52 boys and 18 girls with autism as well as to 26 and 36 typically developing boys and girls, respectively. Using eye-tracking technology, they were able to capture where on the screen children looked during the entire clip.

Overall, both girls and boys with autism looked less often at the eyes compared with typically developing kids, consistent with previous studies. The amount of eye contact from the boys related directly to their overall level of social disability. Boys who looked less at the eyes were more socially disabled.

Girls with autism, however, showed the opposite pattern: Those who focused relatively more to the eyes tended to experience worse social disability, said Jennifer Moriuchi, an Emory psychology graduate student.

The team found significant differences in timing of when girls or boys would look at the eyes, suggesting they aren’t following the same cues.

The group is continuing with its work to understand these differences in engagement with the eyes, which highlights just how little is known about how autism manifests in girls, said Warren Jones, research head at the center.

“We tended to assume that boys and girls [with autism] do the same thing when they adjust to everyday life,” Dr. Klin said. “There’s emerging evidence that it’s to the contrary.”

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324326504578466920841542396.html

Related Posts:

Women and Girls On The Autism Spectrum

Autism: It’s Different For Girls

Related articles

- Girls With Autism May Need Different Treatments Than Boys (news.health.com)

Keep Autism Awareness Alive: Help Prevent The Reality Of Falling Off A Cliff

These are two stories that typically merit separate posts, but they clearly share a central theme and so I decided to put them together. Growing up on the Autism Spectrum is difficult; for the individual, for parents, educators, siblings and friends. It is made (relatively) easier by the degree to which that individual has support; financial, emotional, institutional or otherwise. The harsh reality of new-found adult status can be jarring, if not entirely all-consuming and down-right depressing at times. Gone are many of those supports that each individual has literally needed to make the progress that they have. Gone also are many of the dreams of childhood; that unique innocence that sparks each autistic child to work towards something off in the distance.

As a society, we need to have a plan to integrate young adults on the spectrum into that same civilized society. Assistance with job placement? Yes! Easier access to (more) Day Habilitation Programs? Yes again! Autism insurance reform? Hell yes!

Autism awareness efforts can no longer be a grass-roots effort. It must be a concerted, unified attack that has the full backing of local, state and federal agencies. No autistic child who grows into adulthood should ever have to fend for himself to receive the same considerations that their neuro-typical peers get.

On this last day of Autism Awareness Month, let’s all give our kids (children and adults alike) a hug, a kiss and a promise to keep their hopes and dreams, as well as their rights, alive. -Ed

KIDS WITH AUTISM “FALL OFF THE CLIFF” AFTER GRADUATION

For four years, Janet Mino has worked with her young men, preparing them to graduate from JFK High School, a place that caters to those with special needs in the heart of one of the poorest cities in America, Newark, N.J.

All six of them have the severest form of autism, struggling to communicate, but Mino’s high-energy style evokes a smile, a hug and real progress.

Much of the work that she does may ultimately unravel because after these young men earn their diplomas, their future options are bleak — lingering at home, being placed in an institution or living on the streets.

New Jersey has the highest rate of autism in the nation and some of the best intervention resources. But after graduation, programs are scarce.

“They are adults longer than they are children,” Mino, 46, told ABCNews.com. “We need to give them a light. It’s up to us and up to me.”

“There’s nothing — nothing out there,” she said.

Mino, a whirling dervish of enthusiasm and warmth, is the subject of a documentary, “Best Kept Secret,” that recently premiered at the Independent Film Festival in Boston and will be shown at this weekend’s Montclair Film Festival in New Jersey.

Mino’s efforts to find resources for her students are Herculean in a school that is touted as the state’s “best kept secret.” Her efforts are exacerbated by poverty and lack of funding, but her classroom is a happy place as she finds ways to reinforce that they are capable and worthy.

“I look at it as a challenge — if I can get them as independent as possible,” she said. “They are so wonderful. They make you laugh. … They just think differently.

“Some people think that because they are nonverbal and can’t communicate, they can’t understand, but that’s not true. From my experience, they read us better than we read them.”

Director Samantha Buck [“21 Below”] and producer Danielle DiGiacomo, who is manager of video distribution at the Orchid, follow Mino and her students in their hardscrabble lives for 18 months leading up to their 2012 graduation.

“Autism is part of who we are as a society,” said Buck, 30. “Across the country, young adults who turn 21 are pushed out of the school system. They often end up with nowhere to go; they simply disappear from productive society. This is what educators call ‘falling off the cliff.'”

This year alone, 50,000 children with autism will turn 18, according to Sen. Robert Menendez, D-N.J., who has sponsored federal legislation to provide funding for adult programs. Within two years of high school, less than half of those with autism spectrum disorder have paying jobs, the lowest rate of any disabled group.

“Meanwhile, adults with ASD run the highest risk of total social disengagement,” Menendez told ABCNews.com in an email. “By the time they are in their early 20s, they risk losing the daily living skills they developed as children through supportive services.”

“Their families still need support,” he said. “The challenges they face will not disappear but only grow greater, and ultimately we will all pay the price for that.”

Today, an estimated 1 in 50 U.S. school-age children are diagnosed with some form of autism, a number that has been on the rise, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But the filmmakers said they did not want to focus on the “causes of autism and why.”

“Here are these human beings and they live in our world and are part of our society,” said Buck. “How do we integrate this huge population into our society?”

While on the festival circuit, Buck noticed the industry’s interest in films about autism.

“I pretty much cried at every single one,” said Buck. “They were predominantly centered around young Caucasian families with money.”

The filmmakers looked for an inner-city school that would tell a different story. With the help of Menendez, they found JFK High School, where they followed Mino’s students.

But funding is just part of the problem. Many of her students come from dysfunctional families that are challenged by poverty and lack of support.

Erik, the highest-functioning student in the group, is smart, talkative and great at following directions. He may be the most likely to make it in the real world. But his biological mother is too sick to care for him and he relies on a dedicated foster mother.

Robert’s home life is chaotic and it is reflected in his classroom work. He can read and spell, but is frequently absent. His father home-schooled him until dying four years ago. Now, an aunt, a recovering drug addict, looks after him.

Quran is the only one being raised by both his parents. He is able to read and control all of his behaviors, but his family doesn’t know where to turn for help.

“His parents spend every minute of the day thinking about him and his life,” said film producer DiGiacomo. “But they have to put food on the table and there is no time to access information on places where he can go.”

Parents work full time and need placement for their children when they go to work. Programs are costly and navigating the bureaucracy is difficult.

After-school recreation centers only operate from 10 to 1, impractical hours for working parents. And some families don’t even have cars.

“These are the simplest things that we don’t think about that can make or break families,” said Buck. “But they don’t have a woe-is-me [attitude]. This is their life and they love their children.”

Erik works hard when given direction and takes on a part-time job cleaning at Burger King.

“Everybody loves him,” said Buck. “They are good workers. This is not charity.”

But students need work coaches to help with the transition into a job, and Erik’s coach has 100 other clients.